Gentrification, a term which was coined by Ruth Glass (1964), originally refers to an urban process that involves property price increase and replacement of working-class residents by the incoming middle classes. Geographers think that gentrifying areas have distinctive gentrification ambience, which is the cultural characters that appeal gentrifiers and incubates gentrification. Ley (2001) pointed out that gentrifiers love living in inner cities because these places represent a social distinction that separates them from the mundane suburbs. Jager (1986) further attributed the social distinction to a distinctive ambience of gentrifying areas and called it gentrification aesthetic. Researchers after Jager thought that gentrification aesthetic is embodied in a specific art style such as historical or Victorian buildings (Carpenter & Lees, 1995; Jager, 1986), “postmodern landscape” (Mills, 1988), and marginal and bohemian art (Zukin, 1989). According to these discussions, art is one of the main components of gentrification ambience. Yet, not only the art style but also artists and aestheticisation process comprise the special “feel” in a gentrifying place (Ley, 2003).

Specific demographic population and business also contribute to the distinctive gentrification ambiance. Those populations include young people (Ley, 1986; Van Criekingen, 2009), hipsters (Vermeulen, 2016), and gay and lesbian communities (Castells, 1983; Knopp, 1990; Lees et al., 2008; Rothenberg, 1995). For instance, Florida (2002) developed the "gay index" for measuring the tolerance and creative atmosphere of a city. The certain business is related to leisure activities such as trendy restaurants, galleries, cafés, coffee shops, bars, and yoga (Kern, 2012; Ley, 1986; Papachristos et al., 2011; Zukin, 2014).

We assume that a gentrifying area should have gentrification ambience similar to other gentrifying areas, and the places with similar ambience should have similar word usage on their social media posts. Therefore, this project aims at differentiating gentrifying areas from others based on their text similarity.

In this project, the census block groups in our study area, Salt Lake City, were clustered into 7 groups by applying text clustering technique to their Instagram text. The census block groups clustered into the same group mean Instagram posts in these places have higher similarity with each other. The code used for text clustering can be found on my Github.

The web map below shows the text clustering results. Please explore the results from 2013 to 2015 by switching different layers.

Click each group on the map! A word cloud based on its Instagram text shows up, and you will find that there are more gentrification-related words (such as night, coffee, yoga, restaurant, beer, bar, art, and brunch) in Group 5 and Group 7.

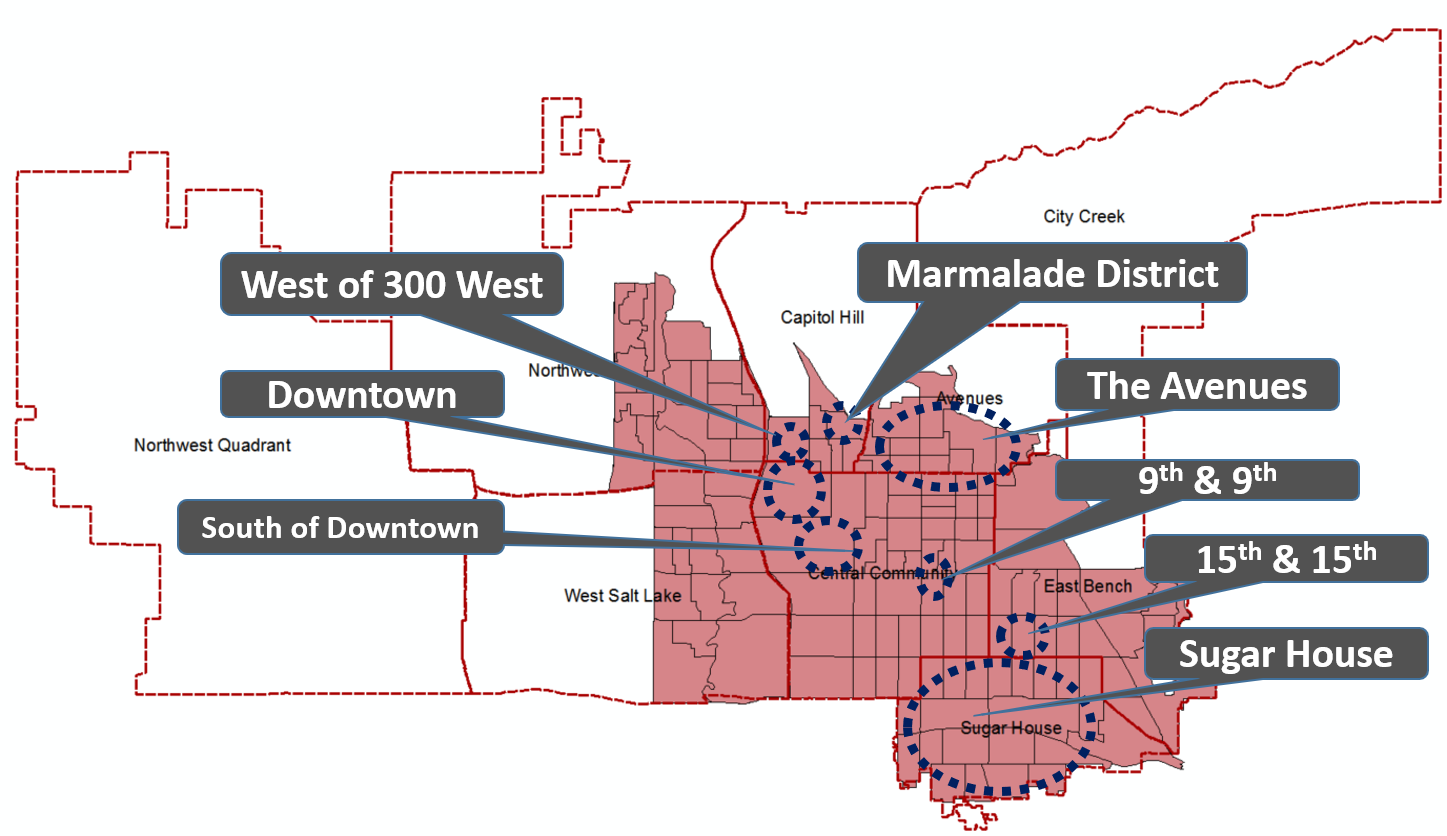

- The image on the right side is the identified gentrifying areas mentioned in news reports and online discussions. In other words, they are human-perceived gentrifying areas. By comparing this image with the web maps of Instagram text clustering, you can notice that the distribution of Group 5 (orange area) and Group 7 (red area) closely correspond to each other. This finding indicates that we are able to differentiate gentrifying areas from other areas using text clustering technique. Also, by taking a close look at the layers from 2013 to 2015, you will also notice the increase of Group 5 and Group 7, which reveals the areas with gentrification ambience were expanding!

Human-perceived Gentrifying Areas in SLC

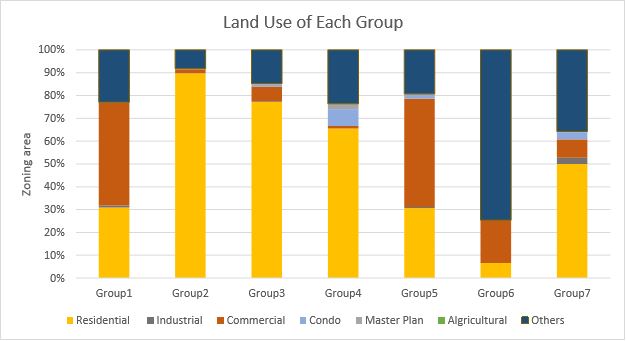

- The other interesting finding is that Group 5 and Group 7 (the groups match human-perceived gentrifying areas) have the different type of land use. The stacked bar chart on the right side shows the land use of each group. In this chart, Group 5 has a higher percentage of commercial area, while Group 7 has a higher percentage of residential area. It indicates that two types of gentrifications have happened in the study area, residential-driven and commercial-driven gentrifications.

Land Use of Each Group

(source: Planning and Development Services, Salt Lake County)

- Reference

- Carpenter, J., & Lees, L. (1995). Gentrification in New York, London and Paris: An International Comparison. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 19(2), 286–303.

- Castells, M. (1983). The city and the grassroots : a cross-cultural theory of urban social movements. London: Arnold.

- Florida, R. (2002). Bohemia and economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 2(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/2.1.55

- Jager, M. (1986). Class definition and the esthetics of gentrification: Victoriana in Melbourne. In Gentrification of the City (pp. 78–91). Boston, MA: Allen and Unwin.

- Kern, L. (2012). Connecting embodiment, emotion and gentrification: An exploration through the practice of yoga in Toronto. Emotion, Space and Society, 5(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2011.01.003

- Knopp, L. (1990). Some theoretical implications of gay involvement in an urban land market. Political Geography Quarterly, 9(4), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(90)900337

- Ley, D. (2001). The new middle class and the remaking of the central city. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press.

- Ley, D. (2003). Artists, aestheticisation and the field of gentrification. Urban Studies, 40(12), 2527–2544. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000136192.

- Ley, D. (1986). Alternative Explanations for Inner-City Gentrification: A Canadian Assessment. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 76(4), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1986.tb00134.x

- Mills, C. A. (1988). “Life on the upslope”: the postmodern landscape of gentrification. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 6(2), 169 – 189. https://doi.org/10.1068/d060169.

- Papachristos, A. V., Smith, C. M., Scherer, M. L., & Fugiero, M. A. (2011). More coffee, less crime? The relationship between gentrification and neighborhood crime rates in Chicago, 1991 to 2005. City and Community, 10(3), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15406040.2011.01371.x

- Rothenberg, T. (1995). “And she told two friends”: Lesbian creating urban social space. In D. Bell, G. Valentine, & J. Silk (Eds.), Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities (pp. 165– 181). London: routledge.

- Zukin, S. (1989). Loft living : culture and capital in urban change. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Zukin, S. (2014). Loft living : Culture and Capital in Urban Change. New Brunswick New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.